Community engagement

When an asylum seeker is granted Leave to Remain in the UK, they become eligible for mainstream benefits and are also granted the right to work. Leave to Remain is usually Refugee Status, but may also be, in a small number of cases, Discretionary Leave or Humanitarian Protection.

Having Leave to Remain in the UK is, however, not the end of their problems. First of all, they have to leave their asylum accommodation within 28 days. This means finding alternative accommodation at the same time as registering for benefits or seeking employment. This would be difficult enough for someone born and bred in the UK – for a refugee who often has not had the opportunity to learn good English, it is extremely difficult to navigate a complex accommodation procedure.

Although the Home Office has made improvements in the system by sending their National Insurance Number along with the Biometric Resident Card and phoning the refugee to arrange an appointment with the Job Centre, often the refugee will find themselves homeless at the end of the 28 days.

There are many reasons for this:

- Delays of several weeks in Universal Credit coming through may leave them destitute

- Opening a bank account may take several weeks,

- Councils often either offer a place in a hostel where they do not feel safe or tell them to seek private accommodation. This is virtually impossible, since they will not have money for a deposit or the first month’s rent.

When they do eventually find a place to live, furnishing it will prove a huge challenge, as will navigating the confusion of utilities and council tax. If the accommodation is in a new area, there will be the additional challenges of orientation and registering with a new GP.

The refugees who cope with this transition period best are those who have good support networks and people who can guide them through the process, or those who have good English and are familiar with British systems.

Two recent reports, Mind The Gap (2018) and Mind The Gap – One Year On (2019) go into all these issues in more depth.

Negative decisions

“We like to put things in neat boxes… it makes life simpler and easier for us to diagnose what is going on… (but)… people are complex, people’s problems are complex

How we measure issues is by population… that's simple… populations don't change much, they might shrink or grow in size… that doesn't solve where we want to get to…

Communities are a lot more vague, a lot more inconsistent… unless we understand that we'll never understand peoples problems and how to unpack them.

All institutions are there because they have to serve the community, they have to serve the people.”

Lord Kamlesh Patel on the Community Engagement Model

What is effective community engagement?

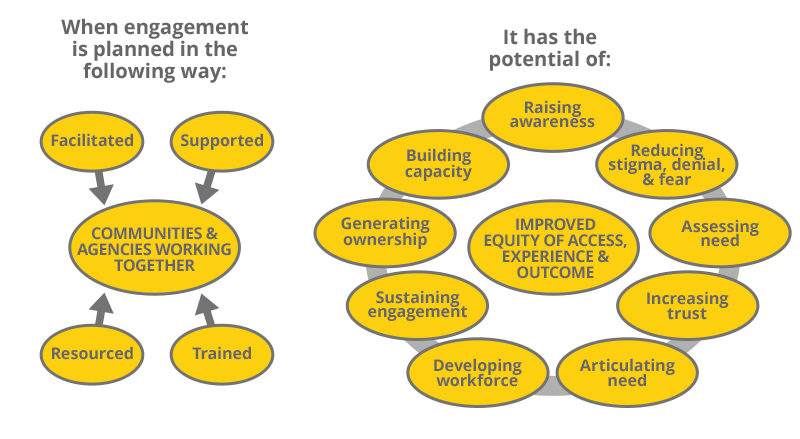

Reference: Centre for Ethnicity and Health

Community Engagement Model 2007

For successful community engagement good planning, the right time and place, and good support is the key.

See the Resource section for toolkits and how to guides.

The following section will provide you with six key aspects of a successful community engagement project as told by one of the facillitators.

1. Why did you choose community engagement for this project and how did it work?

- We felt it was the best way to get agencies speaking directly with refugee communities.

- We chose to work with specific language groups instead of a one size fits all approach.

- We supported community organisations to arrange a series of events for their own community members to strengthen capacity, trust and relevance.

- The events attended by NHS providers, allowed groups to talk and learn from one another

2. You say it is a simple idea, but in reality was it that straightforward?

- No! Broad experiences of health and health care assistance at home and in the UK meant that we had to adapt the model and provide support before the events could take place

- Initial focus groups ensured that each event was suited to the community.

- We understood that health might not be a priority for community organisations.

- We invested in each community organisation through training (e.g. facilitation, meeting skills) and covering costs to strengthen their impact and value their input.

- Simple approaches still need time and investment in people to work well.

3. Apart from this investment, how else can you ensure the engagement is productive and focused?

- Be clear about the reasons for the project, its capacity, duration and objectives.

- Plan contingencies in advance: for example, know how to and where to signpost people if you cannot respond to their concerns due to your remit/capacity.

- You will be more effective in discussing outcomes, expectations and boundaries having considered this.

- Do what you say you were going to do when you said that you would. This avoids undermining current and future projects.

4. Some individuals/agencies might not be able to allocate that amount of time, how can these still engage with local communities?

- Work smarter.

- Link up with the others who are already engaging with local communities.

- This is good for your time and resources - and those of the community organisations and members you want to engage: avoid ‘engagement fatigue’!

5. How do I find out what is going on in my local area? Why is this important?

- Make sure you are not duplicating work and ask questions to help you plan your work better.

- Your own organisation: contact the person responsible for consultation/engagement for an overview of what work is being done and with whom.

- The local authority: what are their neighbourhood/community teams doing and what existing partnerships do they have to engage through nonstatutory organisations?

- The voluntary sector: talk to your local authority/strategic planners about existing links and networks.

- Download this Gathering Relevant Information document for more ideas.

6. Can you give an example from this project of the positive impact for both patients and the health service?

- ‘A’ is a leading member of a Cote D’Ivoire community organisation.

- At a project event he spoke with representatives of the A&E and community pharmacy services, among others.

- He gained the information to be able to successfully signpost a community member with a sick child the following weekend.

- This saved time and resources for both the woman and the health service.

How do these ideas relate to your service?

Think about the work that you and your colleagues do.

| In what ways are you already engaging with the community? | |

|---|---|

| To what extent does this engagement include migrants? | |

| What do you think the barriers are to those migrants engaging? | |

| Which of the inputs described in this unit could help you improve this situation? | |

| What three things could you do to better engage with local migrant communities? |

You can download this table.

Please print it out and fill in the section on the right.

Building multi-agency networks and partnerships

Networks enable people and organisations to interact, to offer support and to focus on issues across geographical or special interest areas. The Interaction and communication through these networks can broaden what we can achieve.

Partnerships are a more formal network where partners agree to work towards shared goals and will commit to different degrees to one another depending on objectives, capacity, resources and commitments.

Problem:

Evidence shows that nutrition levels among new migrants fall upon arrival in the UK.

Question: How is it possible to reach those individuals who we continue to miss through our normal engagement work and help to raise their nutrition levels?

Salford Food Programme

In Salford, the local museum worked on a Food Programme in partnership with the local college, local PCTs and non-statutory organisations, both health and community based.

The PCTs Health Development Worker coordinated Healthy Eating stalls at the museum, supporting and involving volunteers and local groups to take part in the events. They were also involved in health events in the local area and co-planned Refugee Week events.

The partnership generated useful feedback on perceptions of food and difficulties in eating well, such as:

- Participants highlighted the fact that in their own countries, food was generally fresh, you could even pick food on the way to the local market. Here, food is packaged, ‘boxed in’. Some people, particularly young men, said they had bought food in boxes without knowing what was inside and had wasted the little money they had to live on in this way.

- Some mothers stated that they were under pressure from their children to cook ‘British’ food but did not know how to. People said they wanted to understand British food and how to cook it using fresh ingredients.

Read through the questions below and select the statements you think are true. You may select more than one statement.

Q1. Why might a project team which involves the museum staff have more luck than a statutory healthcare provider in gaining information about food choices and sharing health messages?

They are better at their jobs

They work in the community and are not perceived as part of the authorities

They meet regularly with community members and have established trust

The places they meet may be seen as less threatening

Q2. But I'm busy enough as it is. Why is working together useful?

To share resources to reduce barriers and avoid duplication

To be more effective targeting barriers and gaps through more holistic planning

To make the results of work more sustainable

To ensure good referral networks

To learn from a broader perspective

To have a stronger connection with the community you want to engage

Q3. Who might we work with?

Health-based agencies, both statutory and non-statutory

Migrant-led organisations

Advice centres, dealing with broader legal and social needs

Whatever works in terms of understanding and addressing the needs and support systems of the group you want to work with

Making Progress

HOW should we develop good partnerships and multi-agency work?

COMMON PROBLEMS

- Our partnership seems to be nothing more than a talking shop. What can I do to get things moving?

- Our meetings are dominated by two or three vocal people. What can we do?

- No one around here agrees on anything, it’s just politics and back-biting. How can we ensure people are accountable?

SUCCESSFUL FRAMEWORK

- Clarity of purpose and role: This might seem like common sense but, in our experience, it is rarely common practice.

- The capacity to influence and be influenced: the key to developing successful working relationships is to recognise the difference between control and influence.

- Systems and structures that are fit for purpose.

- The capacity and resources to take action.

OPEN

LISTENING

- Sometimes the people we least want to empathise with are those we need to listen to the most.

- We need to draw out concerns without passing judgement.

- Make choices and base actions on information rather than assumptions.

The following diagram demonstrates how working together can progress.

You can download a PDF of it here.

It is important to note that partnerships which remain at the network stage still hold value.

| Network | Coordinate | Cooperate | Collaborate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange information | Exchange information | Exchange information | Exchange information |

| Harmonise activities | Harmonise activities | Harmonise activities | |

| Share resources | Share resources | ||

| Enhance capacity | |||

| Example: A hospital and a community clinic share information about their respective paediatric services. | Example: The hospital and community clinic alter their schedules in order to expand the total hours of operation available for paediatric services in the community. | Example: The hospital and community clinic agree to share physical space and funding for paediatric services in order to expand the range and depth of services provided to their common clients. | Example: The community clinic provides screening and prevention services and refers clients to the partner hospital for follow-up care. The hospital provides the community clinic with technical assistance in a new screening procedure, while the community clinic provides the hospital training in providing culturally competent care. |

Video: How practical partnership working can increase access to mental health support.

As you watch, note down the examples of Networking, Coordination, Cooperation and Collaboration.

Lastly, think about your own service. It might be useful to discuss as a group the potential productive partnerships which could help you reduce barriers to your service and increase awareness and impact.

In the table below, the first couple of examples have been done for you.

Please download our handout PDF and print a copy to fill in the rest.

| Organisation / service type | Nature of partnership | Impact on accessibility of service | Type of work which could be done |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local schools: primary & secondary | Eg: networking to exchange information about language needs to ensure good interpreter provision | ||

| Housing providers: private landlords, social landlords, NASS contract holders | Eg: coordination to ensure new arrivals in the area are provided with a welcome pack with GP registration information | ||

| Non traditional health spaces: museums, galleries, theatres etc. | |||

| Non-statutory organisations, eg: local drop-in centres, migrant support/community groups, health interest groups etc. | |||

| Places of worship, places of congregation | |||

| Other healthcare providers |

Summary

- Community engagement is essential to understand the decision making and evolving nature of the communities in your area.

- Community engagement needs patience, persistence and planning to be effective and productive.

- There are different levels of multi-agency networks and partnerships - all of which can be of use in developing flexible, appropriate and informed services.

- Service improvements can be made in spite of financial constraints.

This module is based on practical exercises to reduce barriers to access.

Now you have completed the module, you should be:

- Aware of what ‘access to services’ means

- Able to clarify the myths surrounding provision and barriers

- Aware of the barriers to access, where they stem from and their impact

- Able to develop practical methods of reducing barriers to accessing services

- Aware of sources of information to build on your awareness and practical resources to assist you in your work