Introduction

Refugees and migrants are, almost by definition, resourceful, resilient and courageous – they have had to be to reach the UK. This resilience provides a considerable measure of protection against the development of mental health problems, but for some individuals the stresses inherent in migration, particularly forced migration, may prove too much to bear, and mental health problems such as clinical depression, anxiety or the symptoms of post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may develop.

Refugees and migrants are, almost by definition, resourceful, resilient and courageous – they have had to be to reach the UK. This resilience provides a considerable measure of protection against the development of mental health problems, but for some individuals the stresses inherent in migration, particularly forced migration, may prove too much to bear, and mental health problems such as clinical depression, anxiety or the symptoms of post- traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may develop.

Mental health and physical health are indivisible, and are only presented separately in this resource pack for convenience.

This module does not set out to give you a list of mental health problems suffered by migrants. Instead, it will help you to understand the possible causes of the psychological distress.

This unit is introductory – further information can be found in the resources section here.

Key points

- Distress is not a ‘mental health problem’ but a normal response to highly abnormal circumstances.

- Issues of loss may be more important than ‘trauma’. Don’t assume the cause of distress.

- Prevention is fundamental - it is very difficult to treat mental health problems in someone who speaks little English.

- Mind your language - ‘mental health problem’ may be interpreted as ‘mad’.

- Counselling and psychotherapy may not be appropriate, but listening and bearing witness is usually acceptable.

Take care of your own mental fitness; hearing extreme experiences can be harrowing, and vicarious trauma is a possible consequence.

"You have come from a country where you were someone, and you have come to a country where you are no-one."

Iraqi refugee Manchester 2010

The 3 stages of exile

The journey into exile can be divided into three stages, with stressors to mental health at each stage. Click on each one to find out more:

- The situations that force a person to flee the security of their own home, friends and community, can be extreme and the effects long lasting.

- These experiences may include experiences of war and civil unrest, persecution, witnessing or experiencing atrocities, and torture.

- Traumatising and injuring experiences can often have been sustained over long periods, with fear and terror becoming normalised into everyday life.

- Many people will have had to flee several times, and spent years in refugee camps, several generations with only ancestral memories of their homeland.

- Often there was no single event which caused the flight but a long history of war, conflict and persecution

- Escaping war and persecution presents further dangers and may result in further physical and psychological harm.

- Escape is hazardous, and individuals often are abused along the way.

- People smugglers have little regard for the wellbeing of their ‘cargo’, and cramped conditions, lack of food, water and poor hygiene may spread parasites and disease and can often result in injury or death.

- Rape and/or physical abuse is common.

- Studies have shown that the massive social loss and consequent grief, social isolation, insecurity and the purposelessness of life in exile can be more damaging to mental health, and more likely to lead to depression, than the experience of trauma in the country of origin (Gorst-Unsworth and Goldenberg 1998, Ager et al 2002, Carswell et al 2011).

- The stressors of exile are chronic and on-going and can be debilitating.

- Refugees and vulnerable migrants may be subjected to hostility, and racism both covert and overt.

- Many suffer considerable social deprivation and marginalisation; isolation and loneliness are common.

- Prolonged separation from, and grieving for, family members and friends. Refugees may never see their families again, may be unable to care for their children, or for their ageing parents. This causes immense distress.

- Loss of status and a purpose in life can lead to a loss of self-esteem.

"When I first arrived, what mattered to me was that someone, anyone, acknowledge me as an individual. It didn’t matter who it was – the bus driver would do."

Iranian refugee woman

Cultural bereavement

Eisenbruch: describes the massive social loss of all that is familiar as ‘cultural bereavement’, and this is probably an inevitable part of exile.

Someone who has fled their country, seeking safety, has lost not only their family and loved ones, but their culture, their community, status, job, home, land, currency, a familiar climate, vegetation, architecture, a society which functions in a way they understand, and a language that is part of their birth-right and in which they can express themselves effortlessly, without having to grope for the right word.

Murphy: "...the sudden violent dispossession accompanying a refugee flight is much more than the loss of a permanent home and a traditional occupation, or the parting from close friends and familiar places. It is also the death of the person one has become in a particular context, and every refugee must be his or her own midwife in the painful process of rebirth."

Launch the video to hear about social and cultural loss.

"Our lives are like the shattered globe at the Imperial War Museum North – we build a new life from the pieces, but it is never the same life. That has gone forever."

Woman from Zimbabwe.

Accessing mental health services

Cultural factors can have a profound significance on an individual’s ability and willingness to turn to mental health services for help with their distress.

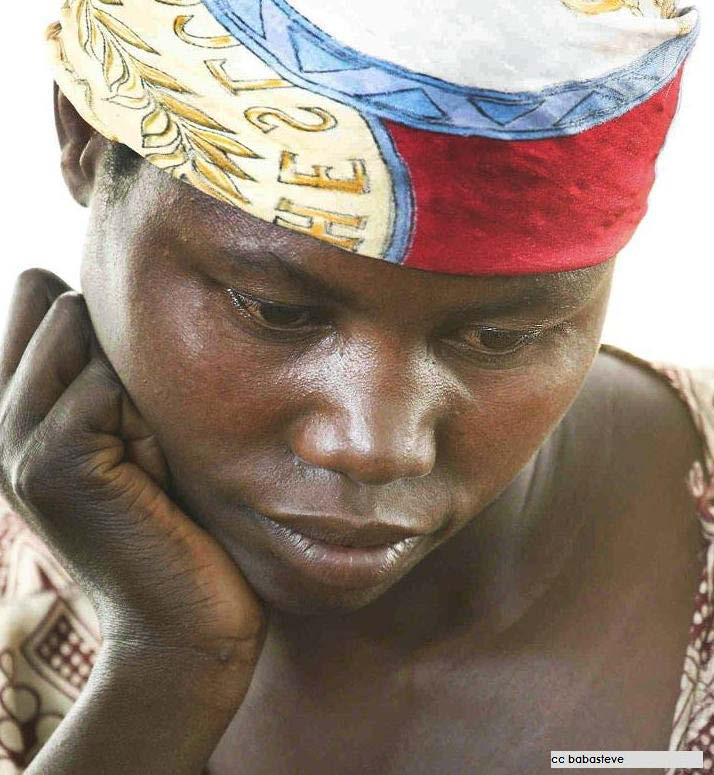

Launch the audio file below to hear a view of mental health from Central Africa.

Understandings of mental health vary greatly between and within cultures, and may be very different to that of professional staff trained in Western systems, leading to mutual incomprehension.

Understandings of mental health vary greatly between and within cultures, and may be very different to that of professional staff trained in Western systems, leading to mutual incomprehension.

The stigma of a diagnosis of ‘mental health problem’ can be profound and may serve to isolate the individual from the support of those he or she would otherwise rely on.

Western culture is largely egocentric, thinking of the individual as autonomous and separate from others. Non-western cultures tend to be more sociocentric, the individual seeing him/herself as indivisibly part of a group, whether family, village or tribe. Because of this fundamental difference talking cures such as counselling and psychotherapy, which assume a degree of autonomy, may not be appropriate, at least in the early stages of life in the UK.

Many people are reluctant to talk about past trauma to strangers, and this may not be a culturally familiar way of dealing with unhappy memories.

"When I first came to the UK counselling would not have helped my sadness, but getting out and about did."

Zimbabwean man

Trust and fear of the betrayal of trust

It takes time to build trust, and you should not expect to do too much in one session. Allowing the individual time to assess you and decide whether they wish to confide in you, maybe by discussing neutral issues, will put some control back into his or her hands.

Disclosure of ill-treatment is very difficult, particularly if there has been a sexual component to the torture. Feelings of shame and guilt can be overwhelming.

The offer of practical support and advice can help to build a relationship, but don’t promise what you cannot deliver.

Explain the concept of confidentiality – that you will not repeat anything to anyone without permission (unless issues of safety override this). The word ‘confidentiality’ does not translate easily into many languages – ‘secrecy’ may be the nearest synonym. People may fear that information about their illness may spread to others in their community, possibly through the interpreter.

Expressions of distress

Distress and emotional states are perceived and expressed differently in different cultures.

Distress and emotional states are perceived and expressed differently in different cultures.

There may be no words for depression, stress etc. because underlying concepts referring to mental states may be very different.

Sadness and worry may be seen as existential problems, part of life, rather than a ‘mental health problem’.

Idioms of distress, the way in which people articulate the way they are feeling, vary between cultures.

There are almost always differences within cultural groups as well as between them.

Always take into account that within the same national groups, differences in levels of education, social class, degree of urbanisation and outlook may mean that individuals adopt different viewpoints; the world view of someone who is highly educated and from a city will, in many ways, differ from a person from the countryside who has received only elementary schooling.

Torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of physical or psychological pain by a person or persons who have power and control over the individual.

As well as inflicting pain, the intention is to humiliate and degrade, to break the spirit.

People who have been tortured often have overwhelming feelings of shame, of being different from others, ‘branded’, and cut off from the rest of society.

These feelings are particularly acute when there has been a sexual component to the torture (as there often is, of men as well as women), and it can be very difficult for the individual to disclose what has happened to them.

Freedom from Torture is a national charity which works with survivors of torture, providing counselling and psychotherapy, practical advice and therapeutic groups. They also offer training on working with torture survivors.

Possible mental health consequences of exile

Common mental health problems may include:

|

Headaches |

Very common among people who are distressed, often they may be due to muscle tension and difficulty relaxing |

|

Difficulty in sleeping |

Many people have great difficulty in falling asleep, and often wake again after a very short time, with distressing thoughts churning in their mind A lack of sleep can become chronic |

|

Panic attacks |

Panic attacks can be very frightening and require explanation of their cause and advice on how to deal with the symptoms |

|

Anxiety and depression |

Be aware that normal distress, grief and worry can become overwhelming and affect an individual’s ability to cope with their everyday life, and develop into depression and/or anxiety. Problems often do not surface until the individual’s life is more settled; acute immediate needs do not allow for reflection on trauma. This may be years after the incidents |

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD is a collection of symptoms indicating increased arousal, including vivid flashbacks to extreme events.

There has been considerable debate about the appropriateness of this diagnosis in the case of refugees.

Others have argued that there is nothing ‘post’ about the traumatic experiences, and that life in the UK can, for some, be as damaging as the trauma of war.

Find further information in NICE guidelines - nice.org.uk

How to listen

"Trust, hope and a purpose in life are the best anti-depressants."

(Bracken 2005)

Despite the reservations discussed previously about the appropriateness of counselling for new arrivals, listening, bearing witness, validating experiences and acknowledging human rights abuses are usually acceptable, and can be very helpful.

The experiences related may be difficult to hear. If an individual with whom you are working trusts you sufficiently to talk about what has happened to them, try to listen. It will have taken a great deal of courage to reach this point, and the message, implied or stated, that the story is too horrific for you to cope with reinforces the feeling that what has happened cannot be borne, and may increase the feelings of shame which are often part of the psychological sequence of abuse.

Having an interest shown in one’s experiences and being treated with respect as a human being who has had a life before and after the events which caused the exile can strengthen self-esteem.

Take care of your own mental health. Acknowledge that the story can be very hard to hear, and the effect that it may have had on you, and seek clinical supervision, for example from a staff counsellor or line manager.

Helpful responses

Don’t expect to do too much at one session – it takes time to build trust, and these are very complex situations.

Understandings of mental health vary throughout the world, and stigma may be a huge deterrent from using mental health services. Stigma may exacerbate the isolation of the individual.

People often have overwhelming practical problems. Signposting to people or organisations who can help, as well as providing practical help, will help with building a trusting relationship

Take into account the totality of the client’s experiences. The person in front of you had a life before exile.

Support with the physical manifestations of distress such as sleep management relaxation techniques and explanations of the physiology of the fight/flight response can be helpful and will demonstrate that you wish to help.

Take time to brief and de-brief interpreters. The interpreter may have had similar experiences, and hearing descriptions of abuse may be distressing. See Communication (Module2).

Take a community development approach and work with the voluntary sector – that is where the knowledge is. Building the social capital of refugee and migrant groups will enable people to help themselves.

Social causes of distress require social responses – social support is a known protective factor.

Health sector workers cannot address social issues in isolation; joint work with voluntary sector organisations or faith groups is often the best way to help people to rebuild shattered lives and shattered communities. These are resilient and resourceful people.

It is not the person who is broken, it is his or her world.

Key Points:

- Most migrants do not have ‘mental health problems’.

- Prevention is fundamental and is best achieved through social interactions.

- Understandings of mental health vary throughout the world, and stigma may be a huge deterrent from using mental health services.

- Issues of loss may be more relevant than trauma.

- Conditions of poverty, isolation and racism in the UK are chronic and on-going, and can be detrimental to mental health.

- Mind your language! ‘Mental health problem’ may well be interpreted and heard as ‘madness’. Words which are more neutral, such as distress, pain, sadness and worry, will be better understood.